Storage

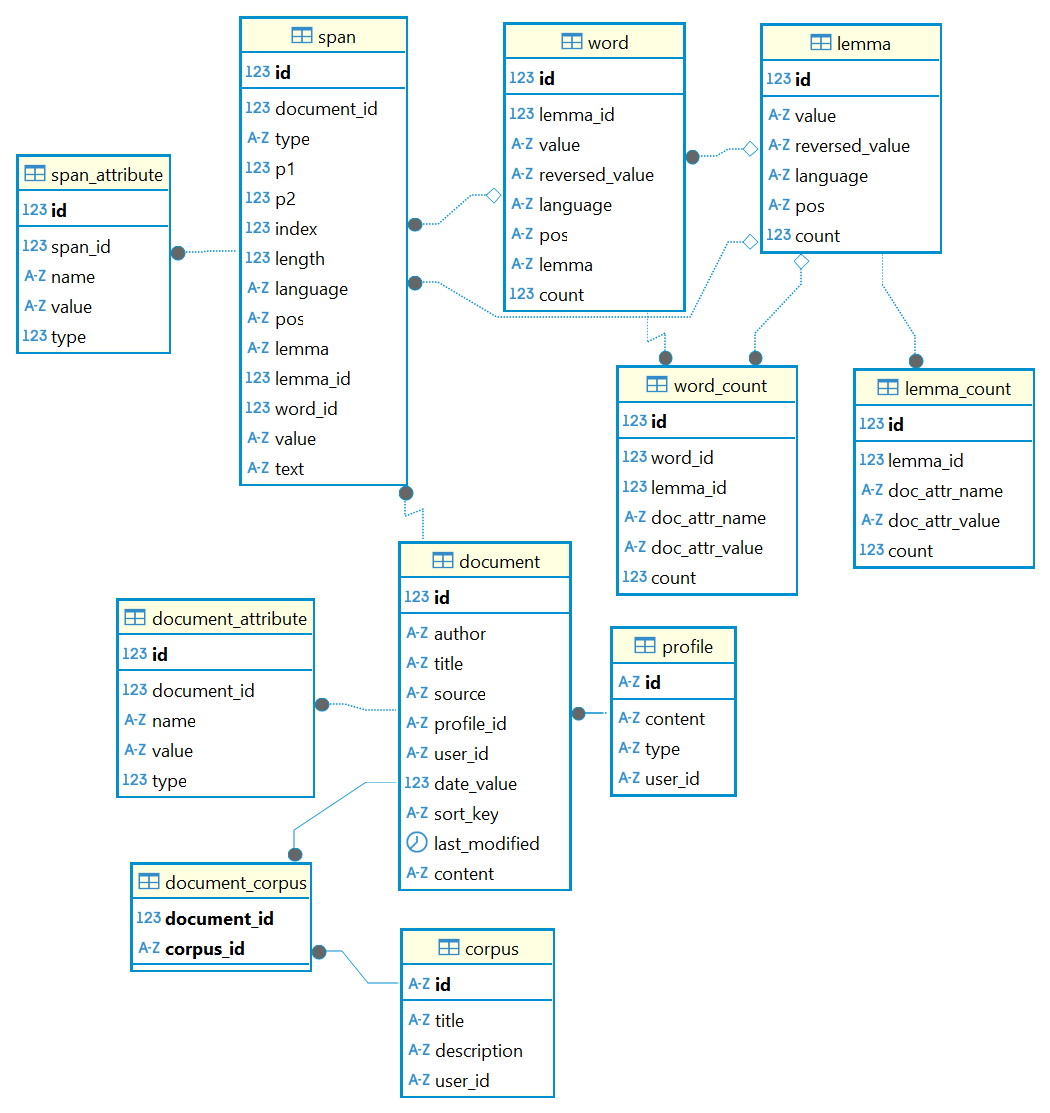

The Pythia index has a simple architecture, focused around a few entities.

Documents

We start with the document (in document). A document is any indexed text source. Please note that a text source is not necessarily a text: it can be any digital format from which text can be extracted, just like in most search engines.

Documents have a set of fixed metadata (author, title, source, etc.), plus any number of custom metadata. In both these cases, metadata have the form of a list of attributes (in document_attribute). An attribute is just a name=value pair, decorated with a type (e.g. textual, numeric, etc.).

Corpora

Documents can be grouped under corpora (corpus via corpus_document), with no limits. A single document may belong to any number of different corpora. Corpora are just a way to group documents under a label, for whatever purpose.

Spans

Each document is analyzed into text spans (span). These are primarily tokens, but can also be any larger textual structure, like sentences, verses, paragraphs, etc. All these structures can freely overlap and can be added at will. A special field (type) is used to specify the span’s type.

Whatever the span type, its position is always token-based, as the token here is the atomic structure in search: 1=first token in the document, 2=second, etc. Every span defines its position with two such token ordinals, named P1 and P2. So a span is just the sequence of tokens starting with the token at P1 and ending with the token at P2 (included) in a given document. Thus, when dealing with tokens P1 is always equal to P2.

Just like documents, a span has a set of fixed (like position, value, or language) and custom metadata (as custom attributes, in span_attribute).

Words and Lemmata

Additionally, the database can include a superset of calculated data essentially related to word forms and their base form (lemma).

First, spans are used as the base for building a list of words (word), representing all the unique combinations of each token’s language, value, part of speech, and lemma. Each word also has its pre-calculated total count of the corresponding tokens.

In turn, words are the base for building a list of lemmata (lemma, provided that your indexer uses some kind of lemmatizer), representing all the word forms belonging to the same base form (lemma). Each lemma also has its pre-calculated total count of word forms.

Both words (in word_count) and lemmata (in lemma_count) have a pre-calculated detailed distribution across documents, as grouped by each of the document’s attribute’s unique name=value pair.

Building Word Index

Word data is calculated as follows:

- for each group of tokens as defined by combining language, value, POS and lemma, store the group as a word.

Words are extracted from all the documents, so this operation must be executed once the documents indexing process has completed. If your database is not too large, you can do this manually by executing the following queries:

-

clear table:

DELETE FROM word;If starting fresh, you might want to reset the PK autonumber after clearing the table:

ALTER SEQUENCE word_id_seq RESTART WITH 1;. -

fill from tokens:

INSERT INTO word (language, value, reversed_value, pos, lemma, count) SELECT language, value, reverse(value) as reversed_value, pos, lemma, COUNT(id) as "count" FROM span WHERE type = 'tok' GROUP BY language, value, pos, lemma ORDER BY language, value, pos, lemma;

💡 Should you need to get the links between words and their tokens, you might want to add a word_span table and fill it like this:

-- word_span

CREATE TABLE word_span (

word_id int4 NOT NULL,

span_id int4 NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT word_span_pk PRIMARY KEY (word_id, span_id)

);

-- word_span foreign keys

ALTER TABLE word_span ADD CONSTRAINT word_span_fk FOREIGN KEY (word_id) REFERENCES word(id) ON DELETE CASCADE ON UPDATE CASCADE;

ALTER TABLE word_span ADD CONSTRAINT word_span_fk1 FOREIGN KEY (span_id) REFERENCES span(id) ON DELETE CASCADE ON UPDATE CASCADE;

-- filling table

INSERT INTO word_span (word_id, span_id)

SELECT DISTINCT w.id AS word_id, s.id AS span_id

FROM word w

JOIN span s ON w.value = s.value

AND (w.language IS NOT DISTINCT FROM s.language)

AND w.pos = s.pos

AND COALESCE(w.lemma, '') = COALESCE(s.lemma, '')

WHERE s.type = 'tok';

In case of bigger databases, or whenever you want to avoid manual updates, a code-based process is used, which adopts data paging and client-side processing.

Once we have words, lemmata data is calculated as follows:

-

group word forms by language and lemma, while summing their counts; each group is a lemma:

INSERT INTO lemma (language, value, reversed_value, count) SELECT w.language, w.lemma AS value, reverse(w.lemma) AS reversed_value, SUM(w.count) AS count FROM word w WHERE w.lemma IS NOT NULL GROUP BY w.language, w.lemma ORDER BY w.lemma; -

once we have inserted lemmata, fill

word.lemma_id:UPDATE word w SET lemma_id = l.id FROM lemma l WHERE COALESCE (w.language,'') = COALESCE(l.language, '') AND w.lemma = l.value AND w.lemma IS NOT NULL;

Lemma index is built from the word index, by grouping word index rows based on their lemma_id.

Managing Data

Here are some useful commands to manage Pythia PostgreSQL databases.

- backup database:

pg_dump --username=postgres -f c:/users/dfusi/desktop/dump.sql pythia

- restore database from a dump like the above (first you must create the database):

psql -U postgres -d pythia -f c:/users/dfusi/desktop/dump.sql

- bulk write for API:

./pythia bulk-write c:/users/dfusi/desktop/dump