Graph Mappings

The mapping between Cadmus source data (items and parts) and nodes is defined by node mappings. This is the core of the projection mechanism, which extracts a subset of source data into a graph of nodes.

The mapping process may have a complex logic: on the source side, it deals with any objects, whatever their schema and complexity; on the target side, it deals with a graph where data are extremely fragmented into the atoms represented by nodes.

Of course, it is up to the scholars to define this mapping, which implies:

- deciding which subset of Cadmus data should be projected into a graph;

- deciding which ontologies to use in the target graph.

This implies that the Cadmus system must be:

- flexible, because it must adapt to any source and target types;

- modular, splitting a monolithic complex logic into many smaller pieces, which fit their source models;

- reusable, providing a totally customizable system where scholars just provide mapping declarations, without having to write code, nor delving into the details of an imperative, step by step procedure.

This is why the graph system is based on a set of mapping rules, each having the task of projecting a small bit of data. These rules are very simple and small, but they can be organized in a tree structure, which nicely fits the structure of Cadmus source data (objects, i.e. trees of properties). So, each mapping rule is the root of a tree structure, where each node is a mapping rule.

Sources

At the input side of mappings, there are two types of sources:

- item: a Cadmus item. You can have mappings for the item; its group; and its facet.

- part: a Cadmus part.

💡 Note that for item titles a couple of conventions dictate that:

- if the title ends with

[#...], then the text between[#and]is assumed to be the UID. The only processing applied to this UID is prepending the prefix defined in the mapping, if any. - if the title ends with

[@...], then the text between[@and]is prefixed to the generated UID. If the mapping already defines a prefix, it gets prepended to this one.

Identifiers

Before illustrating the mapping process, we must discuss the different identifiers used in it. In this document, these are referred to with these abbreviations:

SID(source ID);UID(entity’s URI-based ID);EID(entry’s ID).

From the point of view of the mapping flow, it all starts with a SID, which specifies the source for the mapping.

Mapping rules generate entities which get identified by UIDs. To this end, they may use the EIDs found in source data.

For instance, say we have a Cadmus part representing decorations in a manuscript:

- the source ID for this part is built from its globally unique ID, which is provided for each part. This ensures that this source ID globally refers only to that part.

- each decoration in that part (which is a collection of decorations) has its own EID (entry ID), which is an arbitrarily defined, human-friendly ID like

angel. This entry ID is unique only within the context of that part. - when projecting each decoration entry with an EID (those without an EID are not intended for projection: that’s ultimately the user’s choice), the mapping rule builds a UID for each. This will identify the projected entity for that decoration in the target graph.

Source ID (SID)

The entity source ID (SID for short) is calculated so that the same sources always point to the same entities. The SID is essential for connecting Cadmus data to the entities and keeping them in synch, as it provides the path by which data get added and updated.

The algorithm building the SID is idempotent, so you can run it any time being confident that the same input will always produce the same output. This is ensured by the fact that GUIDs are unique by definitions.

A SID is built with these components:

(a) for items:

- the 36-characters GUID of the source (item).

- if the node comes from a group or a facet, the suffix

|groupor|facet. On passage, note that the group ID can be composite (using slash, e.g.alpha/beta); in this case, a mapping producing nodes for groups emits several nodes, one for each component. The top component is the first in the group ID, followed by its children (in the above sample,betais child ofalpha). Each of these nodes has an additional suffix for the component ordinal, preceded by|.

Examples:

76066733-6f81-48dd-a653-284d5be54cfb: an entity derived from an item.76066733-6f81-48dd-a653-284d5be54cfb|group: an entity derived from an item’s group.76066733-6f81-48dd-a653-284d5be54cfb|group|2: an entity derived from the 2nd component of an item’s composite group.

(b) for parts:

- the GUID of the source (part).

- if the part has a role ID, the role ID preceded by

#.

Examples:

76066733-6f81-48dd-a653-284d5be54cfb: an entity derived from a part.76066733-6f81-48dd-a653-284d5be54cfb#some-role: an entity derived from a part with a role.

Entry ID (EID)

The “entry” ID is just a convention followed in models of Cadmus multi-entity parts.

A Cadmus part corresponding to a single entity is a single “entry”. In this case, its ID is simply provided by the part’s item.

For instance, a person-information part inside a person item just adds data to the unique entity represented by the item (=the person). So, the target entity is simply the one derived from the item. There is no need for an EID here, because the item will already get its own identifier.

Conversely, a manuscript’s decorations part is a collection of decorations, each corresponding to an entry, optionally having its EID (exposed via an eid property). All the entries with EIDs get mapped into entities.

Thus, here we call EIDs the identifiers provided by users for entries in a Cadmus collection-part. When present, such EIDs are used to build node identifiers URIs (UIDs).

This is not the unique purpose of EIDs. In general, this convention provides a mechanism to set a human-friendly identifier for some entity contained in a data model. Often these can also be used to deep-link some data in a model to another one.

Entity ID (UID)

The entity ID is a shortened URI where (like in Turtle) a conventional prefix replaces the namespace, calculated as defined by the entity mapping.

To get relatively human-friendly UIDs, the UID is derived from a template defined in the mapping rule generating a node.

Yet, as we have to ensure that each UID is unique, whenever the template provides a result which happens to be already present and the mapping explicitly requests a unique UID, the UID gets a numeric suffix preceded by #. This suffix is granted to be unique in the context of our data.

💡 By convention, any UID built by mapping and potentially requiring this suffix must end with

##, to indicate that a unique UID via an optional numeric suffix is required. For instance,itn:timespans/ts##means that the first time such a UID is generated it will be stored asitn:timespans/ts; the next time, it will rather be suffixed with a number, e.g.itn:timespans/ts#3.

So, this mechanism ensures that the UID is unique, even though it is specified by users as a human-friendly identifier.

UID Builder

⚙️ TECHNICAL NOTE

The UID is built by a component implementing interface IUidBuilder. A RAM-based implementation of this UID (RamUidBuilder) is provided for testing.

In real world, the implementation relies on a RDBMS database. The table used for it is named uid_lookup, and has these fields:

idPK AI: an autonumber primary key handled by the database engine.sid: the SID linked to the UID.unsuffixed: the UID as generated by the mapping rule, before any suffixation.has_suffix: true if the UID must be suffixed. If true, the numeric value to append to the suffix is represented byid. This trick allows us to efficiently leverage the autonumber capabilities of a RDBMS to append a unique numeric suffix to whatever UID.

So, the RDBMS based implementation of the builder looks in this table for an UID whose unsuffixed form is equal to that being handled. If none is found, the UID is used as such, without any suffix, and stored there with has_suffix=false.

If any is found but the caller requested a unique UID, the UID gets its has_suffix field set to true. This means that effectively the UID of the entity will be equal to the unsuffixed form + # + the value of id.

Mapping Rule

A mapping rule is modeled as an object having a number of properties, defining:

- its metadata (like source type, SID, description, etc.).

- its input (used to match sources).

- its output (which nodes and triples to emit).

In turn, each mapping rule can include any number of children rules. The model as it used in a JSON-based serialization is as follows:

sourceType*: the type of the source object. This is meaningful for root mappings only. The source type is a number:0=user,1=item,2=part,3=thesaurus,4=implicit (assigned to nodes automatically added because used in a triple without yet being present in the graph). Thus, mappings defined in a mappings document effectively use only1and2.sid*: the source ID (SID) of this mapping. This is usually specified at the root mapping level, but you can also override the root sid in your children mappings (almost always this means adding suffix(es) to the root SID). Thus, SIDs are inherited unless overridden in descendants. If a SID includes theindexmetadatum, and the mapper is processing an array, it will be recalculated for each array’s item.facetFilter: an optional item’s facet filter. When specified, the mapping will target only those items whose facet ID is equal to this value.groupFilter: an optional item’s group filter. This is a regular expression; when specified, the mapping will target only those items whose group ID matches this expression.flagsFilter: an optional item’s flags filter. This is a numeric value, where each bit represents a flag. When specified, the mapping will target only those items whose flags include at least all the bits set in this value, i.e. all the flags specified in the filter must be present.partTypeFilter: an optional part’s type ID filter. When specified, the mapping will target only those items whose part type ID is equal to this value.partRoleFilter: an optional part’s role ID filter. When specified, the mapping will target only those items whose part role ID is equal to this value.-

description: an optional, human-readable short description for the mapping rule. This is useful for documentation purposes. source*: the source expression representing the data selected by this mapping. In the current implementation this is a JMES path. For instance,events[?type=='person.birth']matches only the entries in theeventsarray property of a part’s model whose type is equal toperson.birth. When your source expression selects an object, you can refer to it as a whole with., or to any of its properties by their name. When it selects an array, the mapper will implicitly loop through all its items, and be run for each of them. So, you can still define your mappings in terms of a single object, which here is the array’s item. Additionally, theindexmetadatum will be used to represent the index number of the item in the array (0-N).-

scalarPattern: the optional regular expression pattern which should match against a scalar value defined by the mapping’s source expression for the mapping to be applied. When this is defined and does not match, the mapping will not be applied. This can be used to overcome the limitations of the source expression in languages like JMESPath, where e.g..[?lost==true]is always evaluated as a match, even when the value of the scalar propertylostisfalse. So, in this example settingscalarPatterntotrueand source tolostwill apply the mapping only if this property’s value istrue. -

output:nodes: an object (dictionary) where each property is the key of a node emitted by the mapping rule, whose string value is the node’s identifier template. Optionally, this template can be followed by space plus the node’s label, and/or its tag between square brackets, the tag being preceded by|. For instance,x:events/{$.} [label|tag]defines the node’s UID, its human-friendly label, and an optional tag.triples: an array of strings, each representing a triple template. Each triple is in any of these forms:S P O: subject, predicate, object (all URIs);S P "O": subject, predicate, literal object in double quotes;S P "O"@lang: subject, predicate, literal object in double quotes followed by a BCP647 language tag (e.g."sample"@en);S P "O"^^type: subject, predicate, literal object in double quotes followed by a datatype IRI (e.g."123"^^xs:int).

metadata: optional metadata to be consumed in templates. Metadata come from several sources: the source object, the mapping process itself, and these definitions in the mapping.

children: children mappings. Each child mapping has the same properties of a root mapping, except for those which would make no sense in children, as noted above.

💡 The source type is a number where

0=user,1=item,2=part,3=thesaurus,4=implicit (assigned to nodes automatically added because used in a triple without yet being present in the graph). This is not a closed enumerated value, so that you can optionally add new values by just defining new constants.

Templates

Templates are extensively used in mappings to build node identifiers and triple values.

A template contains text with any number of placeholders, delimited by {}, where the opening brace is followed by a single character representing the placeholder type:

{@...}= expression: this represents the expression used to select some source data for the mapping.{?...}= node key: the key for a previously emitted node, optionally suffixed.{$...}= metadata: any metadata set during the mapping process.{!...}= macro: the output of a custom function, receiving the current data context from the source, and returning a string or null.

These placeholders can also be nested. The mapping rules will take care of resolving them starting from the deepest ones.

⚙️ Placeholder resolution is driven by a simple tree shaped representation of the template (

TemplateTree).

Expressions

- syntax:

{@...}

Expressions select data from the source. The syntax of an expression depends on the mapper’s implementation.

Currently the only implementation is JSON-based, so expressions are JMES paths. This is a very powerful selection and transformation language, which should cover most of the mapping requirements.

For instance, say you are mapping an event object having an eid property equal to some string: you can select the value of this string with the placeholder {@eid}.

Node Keys

- syntax:

{?...}

During the mapping process, nodes emitted in the context of each mapping (including all its descendant mappings) are stored in a dictionary with the keys specified in the mapping itself for each node.

For instance, say your event object emits a node for each of its events. The mapping output for each node specifies an arbitrary key, used to refer to this node from other templates in the root mapping’s context.

As a sample, consider this mapping fragment:

{

"id": "events.type=birth",

"sourceType": "part",

"partTypeFilter": "it.vedph.historical-events",

"source": "events[?type=='person.birth']",

"children": [

{

"source": "eid",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"event": "x:events/{$.}"

}

}

}

]

}

Here we map each birth event (as specified by source). For each of them, a child mapping matches the event’s eid property, and outputs a node under the key event, whose template is x:events/{$.} (where {$.} is a metadatum representing the value of the current leaf node in the source tree). So, in this case the generated node will have an UID equal to x:events/ plus the node’s URI.

As a node is a complex object, in a template placeholder you can pick different properties from it. These are specified by adding to the node’s key a suffix preceded by :. Available suffixes are:

:uri= the node’s generated URI. This is the default property; so when there is no suffix specified, the URI is picked.:label= the node’s label.:sid= the node’s SID.:src_type= the node’s source type.

Metadata

- syntax:

{$...}

The mapping process can set some simple metadata in the form of name=value string pairs. These get stored under arbitrary keys (even if some names are reserved), and are available to any template in the context of its root mapping.

Metadata can be emitted by the mapping process itself, or be defined in a mapping’s output under the metadata property. This is an object where each property is a metadatum with its string value.

Currently the mapping process emits these metadata (whose names are thus reserved):

item-id: the item ID (GUID).item-eid(*): the EID of the item, as conventionally defined by the first matching metadatum with name =eidfrom the item’sMetadataPart, if present. As this is the typical lookup mechanism, your consumer code can provide this additional metadatum by opting in via a metadata supplier.part-id: the part ID (GUID).group-id: the item’s group ID.facet-id: the item’s facet ID.flags: the item’s flags..: the value of the current leaf node in the source JSON data. For instance, if the mapping is selecting a string property fromevents/event[0].eid, this is the value ofeid.index: the index of the element being processed from a source array. When the source expression used by the mapping points to an array, every item of the array gets processed separately from that mapping onwards. At each iteration, theindexmetadatum is set to the current index.

⚙️ Additionally, your backend code might use a metadata supplier with extra metadata sources to provide more metadata. A typical source is ItemEidMetadataSource, which adds these metadata:

item-eid: the value of metadatumeidin theMetadataPart(if any) of the current item.metadata-pid: the part ID (GUID) of the metadata part (if any) of the current item.

(*) As an example, see the Cadmus CLI tool code which by default opts into this metadatum with a code like this:

GraphUpdater updater = new(graphRepository)

{

// we want item-eid as an additional metadatum, derived from

// eid in the role-less MetadataPart of the item, when present

MetadataSupplier = new MetadataSupplier()

.SetCadmusRepository(repository)

// from Cadmus.Graph.Extras

.AddItemEid()

};

Macros

- syntax:

{!...}

Macros are a modular way for customizing the mapping process when more complex logic is required. A macro is just an object implementing an interface (INodeMappingMacro), requiring:

- the macro

Id(an arbitrary string). This is used to call the macro from the template. - the

Runmethod, which runs the macro receiving the current data context, the placeholder position in the template and the template itself, and any arguments following the macro’s ID; and returning a string or null.

The macro syntax in the placeholder is very simple: it consists of the macro ID, optionally followed by any number of arguments, separated by &, included in brackets. For instance:

!{some_macro(arg1 & arg2)}

Some macros are built-in, and conventionally their ID start with an underscore. Currently there is only one:

_hdate(json,property): this macro handles a Cadmus historical date and returns either its sort value, or its human-friendly, machine-parsable text value. Its arguments are:- the JSON code representing a Cadmus historical date;

- the property of the date to return:

value(default) ortext.

Filters

Whenever a template represents a URI, i.e. in all the cases except for triple’s object literals, once the template has been filled, the result gets filtered as follows:

- whitespaces are replaced with underscores;

- only letters, digits 0-9, and characters

:-_#/&%=.?are preserved; - letters are all lowercased;

- diacritics are removed.

Should you want to disable this filtering (which is generally not recommended, as this filtering provides fairly common URI forms), start the template with !, which being a preprocessing directive will be discarded from the template itself.

Sample

As a sample, consider a historical events part. This contains any number of events, optionally with their place and/or time, and directly-related entities.

In this sample we have two events:

- the birth of Petrarch in 1304 at Arezzo from ser Petracco and Eletta Canigiani;

- the death of Petrarch at Arquà in 1374.

Sample Data

Our data here come from a Cadmus part. Its serialized form (stripping out some unnecessary clutter) essentially is an array of two event objects, with their properties:

- the first event has type

person.birth; - the second has type

person.death.

Both these event types come from a thesaurus.

{

"events": [

{

"eid": "birth",

"type": "person.birth",

"chronotopes": [

{

"place": {

"value": "Arezzo"

},

"date": {

"a": {

"value": 1304,

"day": 20,

"month": 7

}

}

}

],

"description": "Petrarch was born on July 20, 1304 at Arezzo from ser Petracco and Eletta Canigiani.",

"relatedEntities": [

{

"relation": "mother",

"id": {

"target": {

"gid": "x:guys/eletta_canigiani"

}

}

},

{

"relation": "father",

"id": {

"target": {

"gid": "x:guys/ser_petracco"

}

}

}

]

},

{

"eid": "death",

"type": "person.death",

"chronotopes": [

{

"place": {

"value": "Arquà"

},

"date": {

"a": {

"value": 1374,

"day": 18,

"month": 7

}

}

}

],

"assertion": {

"rank": 2,

"references": [

{

"type": "paper",

"citation": "Rossi 1963 p.123"

}

]

},

"description": "Petrarch died in 1374, July 18 (or 19) at Arquà."

}

]

}

⚠️ Note that here we placed an assertion at the event level, with rank=2, just to keep the example short. In real world, we would rather assign the assertion at a more granular level, to the death date, if we wanted to use an assertion to represent the fact that we can’t be sure about the day (18 or 19; we might also just use a range in the date value, like 18-19). While we can easily reference the same assertion mapping in different parts of the source data, here we just limited ourselves to the event as a whole. To show the assertion mapping in action, we thus decided to add an assertion at that level.

As you can see, each event in the events array is identified by an arbitrarily assigned EID, unique only in the context of this part’s scope.

Each event usually is connected to a place (Arezzo) and a date (July 20, 1304) using a so-called chronotope.

Chronotopes are typically entered in the editor via bricks like those you can play with at https://cadmus-bricks-v3.fusi-soft.com/refs/asserted-chronotope.

Also, each event has a human-friendly description, and a list of related entities, each having a relation type (from another thesaurus), and the ID of the related entity.

So, here:

-

the first event represents an event of type birth, which took place at Arezzo in 1304-07-20, with a couple of related entities for the parents (mother and father). The person who was born (Petrarca) is implicit, as the events part is inside a person item which represents Petrarca.

-

the second event represents an event of type death, which took place at Arquà in 1374-07-18 (or 19). Again, the person took out of existence by this event is implicit.

Sample Mappings

We can arrange some basic mappings to project each event from this part into a node, with linked nodes for classification, attributes, and relations.

Mappings are encoded in a simple JSON document, which can be imported into the graph database. In Cadmus, mappings need to be put in the graph database, but it’s easier to design them in a simple JSON document, to be later imported into it.

The JSON document is an array of mapping objects. Each mapping object is in a documentMappings array, has some properties, and optionally any number of children mappings, nested under their children property. Let us consider these mappings one at a time.

Birth event

{

"namedMappings": {

// ... omitted

},

"documentMappings": [

{

"name": "person_birth_event",

"sourceType": 2, // source=part

"facetFilter": "person", // only for person items

"partTypeFilter": "it.vedph.historical-events", // only for events part

"description": "Map person birth event",

"source": "events[?type=='person.birth']", // only for birth events

"sid": "{$part-id}/{@eid}", // SID = part GUID + "/" + event EID

"output": {

"metadata": {

"sid": "{$part-id}/{@eid}", // store SID for use in descendants

"person": "x:persons/{$metadata-pid}/{$item-eid}" // UID of the person (in item with metadata part)

},

"nodes": {

"event": "x:events/{$sid} [x:events/{@eid}]" // event node

},

"triples": [

"{?event} a crm:E67_birth", // EVENT is-a birth

"{?event} crm:P2_has_type x:event-types/person.birth", // EVENT has_type person.birth (thesaurus)

"{?event} crm:P98_brought_into_life {$person}" // EVENT brought_into_life PERSON

],

"children": [

// ... omitted

]

}

}

]

// ... omitted

}

👉 (1) the first mapping matches any event of type person.birth (see its source property: this is the JMES path). It outputs the event node and triples telling about it that it’s a birth (a CIDOC-CRM class), has-type person.birth, and brought-into-life the person represented by the Cadmus item containing this events part.

Note that in this compact notation the triple is a single string where subject, predicate and object are separated by space.

The event node has its UID built from these components, separated by slash:

- the prefix

x:events(assuming thatxis the prefix for our target ontology); - the events part GUID;

- the event’s EID. This is unique only in the context of its part; but given that the part’s GUID is globally unique and precedes this in the UID, we can be sure we have a globally unique identifier for this event.

For instance, if the part GUID is d162c70d-5787-4ebb-b922-3196518dbd24 and the event’s EID in it is birth, the UID would be x:events/d162c70d-5787-4ebb-b922-3196518dbd24/birth. So, even if we just used birth to identify our event in the events part, that’s a globally unique identifier for it. The prefix and the EID make this UID more human-friendly, as we can see that it’s an event entity and it refers to a birth.

All the other mappings are children of this event mappings, because they map data in the event object model. If you look at the object model as a tree of properties, then having a tree of mappings makes sense.

So, let us examine each child in the children array.

Birth event - description

"children": [

{

"name": "event_description"

},

// ... omitted

]

👉 (2) this child mapping refers to the child property description of the event object. As we typically have a lot of events, it would not make sense to repeat this mapping whenever we want to map the event’s description. Thus, here we just have a reference to a reusable mapping, named event_description. This is found in another section of our JSON document, named namedMappings. This is a ‘dictionary’ object where each property is a mapping with its reference name. This provides templates which are then embedded in the mapping being read, replacing the name reference.

So, here is the corresponding mapping in the named mappings dictionary. It just adds a triple where:

- subject is the event (which got a temporary name of

event, defined above in the tree); - predicate is a CRM-CIDOC predicate:

crm:P3_has_note(assume that we have definedcrmas the prefix for CIDOC-CRM). - object is a literal, equal to the content of the description property (metadatum

{$.}).

{

"namedMappings": {

"event_description": {

"name": "event_description",

"description": "Map the description of an event to EVENT crm:P3_has_note LITERAL.",

"source": "description", // map event.description

"sid": "{$sid}/description", // SID is built from inherited sid metadatum

"output": {

"triples": ["{?event} crm:P3_has_note \"{$.}\""] // EVENT has_note "..."

}

}

// ... omitted

},

"documentMappings": [

// ... omitted

]

}

💡 The expression

{$.}wraps a simple dot, which is the path to the current node. Here,descriptionbeing a string property (thus a scalar value, rather than an object), the current node is just the string’s value, i.e. the description’s text.

So, when reading this mapping, the "name": "event_description" reference will be replaced with the content of event_description (name, description, etc.). This is very convenient because you can reuse mapping templates and make the JSON document much more compact and less error-prone.

Birth event - note

Again, this is a reference:

"children": [

{

"name": "event_note"

},

// ... omitted

]

The corresponding named mapping is:

{

"namedMappings": {

"event_note": {

"name": "event_note",

"description": "Map the note of an event to EVENT crm:P3_has_note LITERAL.",

"source": "note", // map event.note

"sid": "{$sid}/note", // SID is built from inherited sid metadatum

"output": {

"triples": ["{?event} crm:P3_has_note \"{$.}\""] // EVENT has_note "..."

}

},

}

"documentMappings": [

// ... omitted

]

}

👉 (2) this mapping is almost equal to the previous one. It just outputs a triple for the event’s note, which is a free text. The only difference is the source property name. Of course, it’s up to you to decide whether you want to map both the description and the note (which usually is rather an editorial annotation).

Birth event - chronotopes

Again, this is a reference:

"children": [

{

"name": "event_chronotopes"

},

// ... omitted

]

The corresponding named mapping is more complex, and includes a parent mapping with a couple of children mappings. The mapping refers to the chronotopes property of an event, which is an array of chronotopes, each providing date and/or place indications.

{

"namedMappings": {

"event_chronotopes": {

"name": "event_chronotopes",

"description": "For each chronotope, map the place/date of an event to triples which create a place node for the place and link it to the event via a triple using crm:P7_took_place_at for places; and to triples using crm:P4_has_time_span which in turn has a new timespan node has object.",

"source": "chronotopes", // map event.chronotopes (array)

"sid": "{$sid}/chronotopes", // SID

"children": [

{

"name": "event_chronotopes/place",

"source": "place", // map event.chronotopes[i].place

"output": {

"nodes": {

"place": "x:places/{@value}" // node for place (assuming a place's canonical name)

},

"triples": [

"{?place} a crm:E53_Place", // PLACE is-a place

"{?event} crm:P7_took_place_at {?place}" // EVENT took-place-at PLACE

]

}

},

{

"name": "event_chronotopes/date",

"source": "date", // map event.chronotopes[i].date

"output": {

"metadata": {

"date_value": "{!_hdate({@.} & value)}", // date_value is numeric value

"date_text": "{!_hdate({@.} & text)}" // date_text is textual representation

},

"nodes": {

"timespan": "x:timespans/ts##" // timespan node

},

"triples": [

"{?event} crm:P4_has_time-span {?timespan}", // EVENT has-time-span TIMESPAN

"{?timespan} crm:P82_at_some_time_within \"{$date_value}\"^^xs:float", // TIMESPAN at-some-time-within VALUE

"{?timespan} crm:P87_is_identified_by \"{$date_text}\"@en" // TIMESPAN is-identified-by TEXT

]

}

}

]

}

},

"documentMappings": [

// ... omitted

]

}

👉 (3) the chronotopes property is an array. For each item in it, a chronotope, we map its place and date:

- place: map the place’s node, and use it in a couple of triples: as a subject to say that it’s a place, as an object to say that the event took place in that place.

💡 Note that whenever the mapping process emits a node or triple, this does not imply that this will be effectively added to the graph. The node or triple will be added only when they are not already present, because the generated graph will be merged into the existing, much larger one. So, emitting a node for the place ensures that we have it (otherwise, we could not create triples using it), but it will do no harm if that node already exists.

- date: the

datemapping looks more interesting, as dealing with its complex model requires a macro (you can play with this model using the corresponding UI widget in this demo page). We emit two nodes for each date: one with an approximate numeric value, calculated from the historical date model, and useful for processing data (for filtering, sorting, etc.); another with the human-friendly (yet parsable) representation of the date. The logic required for this could not be represented by the simple mapping model, which is purely declarative, and is bound to be simple for performance reasons. Rather, we use a macro, i.e. an external function, previously registered with the mapper (via the Cadmus data profile). Macro are pluggable components, so they represent an easy and powerful extension point. In this case, the macro_hdateis used to calculate the values from the JSON code representing the historical date’s model. The output is stored in a couple of metadata, and then used in the triples.

Birth event - assertion

An assertion is a generic data structure used whenever data are subject to some degree of doubt. An assertion typically provides a numeric rank representing how much you are confident in data, and possibly a generic tag and a set of documental references (for instance, a paper cited about the reconstruction of an event). Each event can have an assertion in its assertion property, which is handled by this mapping.

Again, this is a reference:

"children": [

{

"name": "event_assertion"

},

// ... omitted

]

The corresponding mapping template is:

{

"namedMappings": {

"event_assertion": {

"name": "event_assertion",

"description": "Map the assertion of an event to EVENT x:has_probability RANK^^xsd:short.",

"source": "assertion", // map event.assertion

"sid": "{$sid}/assertion", // SID

"output": {

"nodes": {

"assertion": "x:assertions/as##" // assertion node

},

"triples": [

"{?event} x:has_probability \"{@rank}\"^^xsd:short", // EVENT has_probability RANK^^xsd:short

"{?assertion} a crm:E13_attribute_assignment", // ASSERTION is-a attribute-assignment

"{?assertion} crm:P140_assigned_attribute_to {?event}", // ASSERTION assigned-attribute-to EVENT

"{?assertion} crm:P141_assigned x:has_probability", // ASSERTION assigned has-probability

"{?assertion} crm:P177_assigned_property_of_type crm:E55_type" // ASSERTION assigned-property-of-type type

]

},

"children": [

{

"name": "event_assertion/references",

"source": "references", // map assertion.references (array)

"sid": "{$sid}/assertion/reference", // SID

"children": [

{

"name": "event/references/citation",

"source": "citation", // map assertion.references[i].citation

"output": {

"nodes": {

"citation": "x:citations/cit##" // citation node

},

"triples": [

"{?citation} a crm:E31_Document", // CITATION is-a document

"{?citation} rdfs:label \"{@.}\"", // CITATION has-label VALUE

"{?assertion} crm:P70i_is_documented_in {?citation}" // ASSERTION is-documented-in CITATION

]

}

}

]

}

]

}

}

}

👉 (4) this mapping refers to the assertion object and to its references. In this case, we chose a simple projection of the assertion, still inside the CIDOC-CRM context:

- we assign the event a probability rank.

- if present, we add a citation for each reference, making it a document. Each citation value becomes its label, and the event is said to be documented in the citation document.

Birth event - tag

This is connected to a specific conventional usage of the generic event’s tag in this example. Events have a general purpose tag property, an optional string with arbitrary content which can be used for grouping or tagging the event according to some criteria.

In this example, we assume that the event’s tag refers to a named period, like “early Middle Ages”, “late Middle Ages”, etc. Typically, this comes from a thesaurus. Of course, this is something specific to each project; that’s just a demo.

Again, this is a reference:

"children": [

{

"name": "event_tag"

},

// ... omitted

]

The corresponding mapping template is:

{

"namedMappings": {

"event_tag": {

"name": "event_tag",

"description": "Map the tag of an event to EVENT P9i_forms_part_of GROUP.",

"source": "tag", // map event.tag

"sid": "{$sid}/tag", // SID

"output": {

"nodes": {

"period": "x:periods/{$part-id}/{@value}" // period node

},

"triples": ["{?event} P9i_forms_part_of {?period}"] // EVENT forms-part-of PERIOD

}

}

}

}

👉 (5) this mapping just maps the event’s tag value into a corresponding period, assuming that the value is right the period’s identifier. Thus, it projects a node for the period, and uses a triple to say that the event is part of that period.

Birth event - related - mother

The next mapping is no longer a reference, but it’s a direct child of the event mapping, and matches all the related entities whose relation property has value mother, i.e. the mother of this person.

Of course,

motherhere is just a mock identifier for that relationship. Usually you would get some class identifier, but here we use a single word to keep the example short.

{

// ... omitted

"children": [

{

"name": "person_birth_event/related/by_mother",

"source": "relatedEntities[?relation=='mother']", // map events[i].relatedEntities with relation=mother

"output": {

"nodes": {

"mother": "{@id.target.gid}" // mother node

},

"triples": [

"{?event} crm:P96_by_mother {?mother}" // EVENT by-mother MOTHER

]

}

}

]

}

👉 (6) this mapping matches an entity whose relation to the event is mother, and projects a node for the mother, having as its UID the globally unique identifier already present in source data (under id.target.gid). It then projects a triple which says that the (birth) event is by the specified mother.

Birth event - related -father

A sibling mapping does the same for the father:

{

// ... omitted

"children": [

{

"name": "person_birth_event/related/from_father",

"source": "relatedEntities[?relation=='father']",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"father": "{@id.target.gid}"

},

"triples": ["{?event} crm:P97_from_father {?father}"]

}

}

]

}

👉 (7) this mapping is similar to the previous one; it projects a node for the father, and a triple saying that the event is from the specified father.

Birth and Death Recap

Here is the full JSON document for the mappings for the birth and also the death events (which essentially has the same structure, except that it has no related entities). This document can be directly imported into the database, thus seeding the mappings table, ready to be used by the Cadmus editor.

Usually, mappings are automatically run whenever data are saved in the Cadmus editor. Anyway, the Cadmus CLI tool provides commands to run mappings against a database. This can be used to even regenerate the full graph starting from Cadmus data.

The document includes two main properties:

namedMappings: the dictionary of shared mappings, each keyed by its internal name.documentMappings: the mappings instances, which may include references to the mappings in the above dictionary.

{

"namedMappings": {

"event_description": {

"name": "event_description",

"description": "Map the description of an event to EVENT crm:P3_has_note LITERAL.",

"source": "description",

"sid": "{$sid}/description",

"output": {

"triples": ["{?event} crm:P3_has_note \"{$.}\""]

}

},

"event_note": {

"name": "event_note",

"description": "Map the note of an event to EVENT crm:P3_has_note LITERAL.",

"source": "note",

"sid": "{$sid}/note",

"output": {

"triples": ["{?event} crm:P3_has_note \"{$.}\""]

}

},

"event_chronotopes": {

"name": "event_chronotopes",

"description": "For each chronotope, map the place/date of an event to triples which create a place node for the place and link it to the event via a triple using crm:P7_took_place_at for places; and to triples using crm:P4_has_time_span which in turn has a new timespan node has object.",

"source": "chronotopes",

"sid": "{$sid}/chronotopes",

"children": [

{

"name": "event_chronotopes/place",

"source": "place",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"place": "x:places/{@value}"

},

"triples": [

"{?place} a crm:E53_Place",

"{?event} crm:P7_took_place_at {?place}"

]

}

},

{

"name": "event_chronotopes/date",

"source": "date",

"output": {

"metadata": {

"date_value": "{!_hdate({@.} & value)}",

"date_text": "{!_hdate({@.} & text)}"

},

"nodes": {

"timespan": "x:timespans/ts##"

},

"triples": [

"{?event} crm:P4_has_time-span {?timespan}",

"{?timespan} crm:P82_at_some_time_within \"{$date_value}\"^^xs:float",

"{?timespan} crm:P87_is_identified_by \"{$date_text}\"@en"

]

}

}

]

},

"event_assertion": {

"name": "event_assertion",

"description": "Map the assertion of an event to EVENT x:has_probability RANK^^xsd:short.",

"source": "assertion",

"sid": "{$sid}/assertion",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"assertion": "x:assertions/as##"

},

"triples": [

"{?event} x:has_probability \"{@rank}\"^^xsd:short",

"{?assertion} a crm:E13_attribute_assignment",

"{?assertion} crm:P140_assigned_attribute_to {?event}",

"{?assertion} crm:P141_assigned x:has_probability",

"{?assertion} crm:P177_assigned_property_of_type crm:E55_type"

]

},

"children": [

{

"name": "event_assertion/references",

"source": "references",

"sid": "{$sid}/assertion/reference",

"children": [

{

"name": "event/references/citation",

"source": "citation",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"citation": "x:citations/cit##"

},

"triples": [

"{?citation} a crm:E31_Document",

"{?citation} rdfs:label \"{@.}\"",

"{?assertion} crm:P70i_is_documented_in {?citation}"

]

}

}

]

}

]

},

"event_tag": {

"name": "event_tag",

"description": "Map the tag of an event to EVENT P9i_forms_part_of GROUP.",

"source": "tag",

"sid": "{$sid}/tag",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"period": "x:periods/{$part-id}/{@value}"

},

"triples": ["{?event} P9i_forms_part_of {?period}"]

}

}

},

"documentMappings": [

{

"name": "person",

"sourceType": 2,

"facetFilter": "person",

"partTypeFilter": "it.vedph.metadata",

"description": "Map a person item to a node via the item's EID extracted from its MetadataPart.",

"source": "metadata[?name=='eid']",

"sid": "{$part-id}/{@value}",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"person": "x:persons/{$part-id}/{@value} [x:persons/{@value}]"

},

"triples": ["{?person} a crm:E21_person"]

}

},

{

"name": "person_birth_event",

"sourceType": 2,

"facetFilter": "person",

"partTypeFilter": "it.vedph.historical-events",

"description": "Map person birth event",

"source": "events[?type=='person.birth']",

"sid": "{$part-id}/{@eid}",

"output": {

"metadata": {

"sid": "{$part-id}/{@eid}",

"person": "x:persons/{$metadata-pid}/{$item-eid}"

},

"nodes": {

"event": "x:events/{$sid} [x:events/{@eid}]"

},

"triples": [

"{?event} a crm:E67_birth",

"{?event} crm:P2_has_type x:event-types/person.birth",

"{?event} crm:P98_brought_into_life {$person}"

]

},

"children": [

{

"name": "event_description"

},

{

"name": "event_note"

},

{

"name": "event_chronotopes"

},

{

"name": "event_assertion"

},

{

"name": "event_tag"

},

{

"name": "person_birth_event/related/by_mother",

"source": "relatedEntities[?relation=='mother']",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"mother": "{@id.target.gid}"

},

"triples": ["{?event} crm:P96_by_mother {?mother}"]

}

},

{

"name": "person_birth_event/related/from_father",

"source": "relatedEntities[?relation=='father']",

"output": {

"nodes": {

"father": "{@id.target.gid}"

},

"triples": ["{?event} crm:P97_from_father {?father}"]

}

}

]

},

{

"name": "person_death_event",

"sourceType": 2,

"facetFilter": "person",

"partTypeFilter": "it.vedph.historical-events",

"description": "Map person death event",

"source": "events[?type=='person.death']",

"sid": "{$part-id}/{@eid}",

"output": {

"metadata": {

"sid": "{$part-id}/{@eid}",

"person": "x:persons/{$metadata-pid}/{$item-eid}"

},

"nodes": {

"event": "x:events/{$sid} [x:events/{@eid}]"

},

"triples": [

"{?event} a crm:E69_death",

"{?event} crm:P2_has_type x:event-types/person.death",

"{?event} crm:P100_was_death_of {$person}"

]

},

"children": [

{

"name": "event_description"

},

{

"name": "event_note"

},

{

"name": "event_chronotopes"

},

{

"name": "event_assertion"

},

{

"name": "event_tag"

}

]

}

]

}

Sample Results

Birth

Starting with the birth mapping, we get 5 nodes:

| label | uri | sid |

|---|---|---|

| x:events/birth | x:events/pid/birth | PID/birth |

| x:places/arezzo | x:places/arezzo | PID/birth/chronotopes |

| x:timespans/ts#5 | x:timespans/ts#5 | PID/birth/chronotopes |

| x:guys/eletta_canigiani | x:guys/eletta_canigiani | PID/birth/tag |

| x:guys/ser_petracco | x:guys/ser_petracco | PID/birth/tag |

⚠️ Note that for readability here and below the real part’s GUID is replaced with the placeholder

PID(orpid– unless specified otherwise, URIs by default are lowercased to avoid confusions arising from mixed casing, which is especially important for the underlying data store, based on PostgreSQL, where string comparison by default is case sensitive).

So we have:

- a birth event;

- a place (Arezzo);

- a date;

- a person, the mother Eletta Canigiani;

- another person, the father Ser Petracco.

The projected triples are 11:

| S | P | O | sid |

|---|---|---|---|

| x:events/pid/birth | rdf:type | crm:e67_birth | PID/birth |

| x:events/pid/birth | crm:p2_has_type | x:event-types/person.birth | PID/birth |

| x:events/pid/birth | crm:p98_brought_into_life | x:persons/mpid/alpha | PID/birth |

| x:events/pid/birth | crm:p3_has_note | Petrarch was born in 1304 at Arezzo from ser Petracco and Eletta Canigiani. | PID/birth/description |

| x:places/arezzo | rdf:type | crm:e53_place | PID/birth/chronotopes |

| x:events/pid/birth | crm:p7_took_place_at | x:places/arezzo | PID/birth/chronotopes |

| x:events/pid/birth | crm:p4_has_time-span | x:timespans/ts#5 | PID/birth/chronotopes |

| x:timespans/ts#5 | crm:p82_at_some_time_within | 1304 | PID/birth/chronotopes |

| x:timespans/ts#5 | crm:p87_is_identified_by | 1304 AD | PID/birth/chronotopes |

| x:events/pid/birth | crm:p96_by_mother | x:guys/eletta_canigiani | PID/birth/tag |

| x:events/pid/birth | crm:p97_from_father | x:guys/ser_petracco | PID/birth/tag |

These triples say that:

- the birth event is of type birth (

E67_Birthclass in CIDOC-CRM). - the birth event has a custom extended type, derived from thesauri.

- the birth event brought into life the item identified by the EID metadatum in the item’s metadata part, here

alpha(just a default mock value used in the Studio UI; one could replace it with something more meaningful, likepetrarch). - there is a place node of type place.

- the event took place in this place.

- the event is linked to a timespan.

- this timespan is around 1304.

- this timespan is identified by human-readable text

1304 AD. - the birth event is by mother Eletta Canigiani.

- the birth event is from father Ser Petracco.

💡 Note that in our mapping we intentionally say nothing else about mother and father; not even that they are persons. We just provide their UID, assuming that data about them is elsewhere in the graph. All what we need here is just the identifier to bring them into our triples. As always, if a node with this identifier already exists, it will be used with no change; otherwise, it will be added to the graph.

Death

As for death, nodes are 5:

| label | uri | sid |

|---|---|---|

| x:events/death | x:events/pid/death | PID/death |

| x:places/arqua | x:places/arqua | PID/death/chronotopes |

| x:timespans/ts#12 | x:timespans/ts#12 | PID/death/chronotopes |

| x:assertions/as#14 | x:assertions/as#14 | PID/death/assertion |

| x:citations/cit#16 | x:citations/cit#16 | PID/death/assertion/reference |

- the death event;

- the death place (Arquà);

- the death date;

- an assertion about the event;

- a citation to be linked to the assertion.

The triples are 17:

| S | P | O | sid |

|---|---|---|---|

| x:events/pid/death | rdf:type | crm:e69_death | PID/death |

| x:events/pid/death | crm:p2_has_type | x:event-types/person.death | PID/death |

| x:events/pid/death | crm:p100_was_death_of | x:persons/mpid/alpha | PID/death |

| x:events/pid/death | crm:p3_has_note | Petrarch died in 1374, July 18 (or 19) at Arquà. | PID/death/description |

| x:places/arqua | rdf:type | crm:e53_place | PID/death/chronotopes |

| x:events/pid/death | crm:p7_took_place_at | x:places/arqua | PID/death/chronotopes |

| x:events/pid/death | crm:p4_has_time-span | x:timespans/ts#12 | PID/death/chronotopes |

| x:timespans/ts#12 | crm:p82_at_some_time_within | 1374.63172 | PID/death/chronotopes |

| type: xs:float | |||

| numeric: 1,374.63 | |||

| x:timespans/ts#12 | crm:p87_is_identified_by | 18 Jul 1374 AD | PID/death/chronotopes |

| language: en | |||

| x:events/pid/death | x:has_probability | 2 | PID/death/assertion |

| type: xsd:short | |||

| numeric: 2 | |||

| x:assertions/as#14 | rdf:type | crm:e13_attribute_assignment | PID/death/assertion |

| x:assertions/as#14 | crm:p140_assigned_attribute_to | x:events/pid/death | PID/death/assertion |

| x:assertions/as#14 | crm:p141_assigned | x:has_probability | PID/death/assertion |

| x:assertions/as#14 | crm:p177_assigned_property_of_type | crm:e55_type | PID/death/assertion |

| x:citations/cit#16 | rdf:type | crm:e31_document | PID/death/assertion/reference |

| x:citations/cit#16 | rdfs:label | Rossi 1963 p.123 | PID/death/assertion/reference |

| x:assertions/as#14 | crm:p70i_is_documented_in | x:citations/cit#16 | PID/death/assertion/reference |

These triples say that:

- the death event is of type death (

E69_Deathclass in CIDOC-CRM). - the death event has a custom extended type, derived from thesauri.

- the death event was the death of the person represented by the item (via its EID in the metadata part), i.e. Petrarch.

- the death event has a free text note with value

Petrarch died in 1374, July 18 (or 19) at Arquà.. - there is a place (Arquà).

- the death event took place at that place.

- there is a timespan (for the date of the death event).

- the timespan is around 1374 (the decimal number is due to the calculation of a single numeric value from year, month and day; this makes the date easy to filter or sort).

- this timespan is identified by human-readable text

18 Jul 1374 AD; - the death event has a probability rank of 2. As noted above, this is not the right place for the assertion: we should rather place it in the date, if any. That’s just for keeping the example short;

- the assertion is of type attribute-assignment (CIDOC-CRM E13);

- the assertion assigned attribute to the death event;

- the assertion assigned a property of type E55 (CIDOC-CRM);

- there is a citation of type document;

- the citation has label

Rossi 1963 p.123(the reference); - the assertion is documented in that citation.

So, these are the outcome of the mapping process. The user is not aware of all this: his only task is filling in a form in a UI. This form lists events. Then, whenever he saves his work, the mapping process for the edited part steps in, and generates this graph of nodes. The graph will then be merged to the graph stored in the database. Thanks to the SID, whenever the same part is changed, the mappings will be run again, and the resulting graph will be merged into the existing graph.

Here, the user just filled in a form by entering a couple of events in the events part of the Petrarch person item. This part contains all the relevant events of his life, starting with birth and ending with death. From these data, the mappings automatically projected 10 nodes and 28 triples. Of course, a form with a list of events where you can insert date, place and pick related entities is generally easier to use than having to manually encode all these nodes and triples without necessarily knowing anything about RDF, much similar to the way Cadmus renders full TEI from its data without users having to know about XML. Also, just like in rendering output from the same data we are free to completely change the target TEI scheme, here in projecting graph nodes and links we are free to completely change the target ontologies by just changing our mappings.

To make things easier, a UI is provided also for creating and testing the mappings themselves.

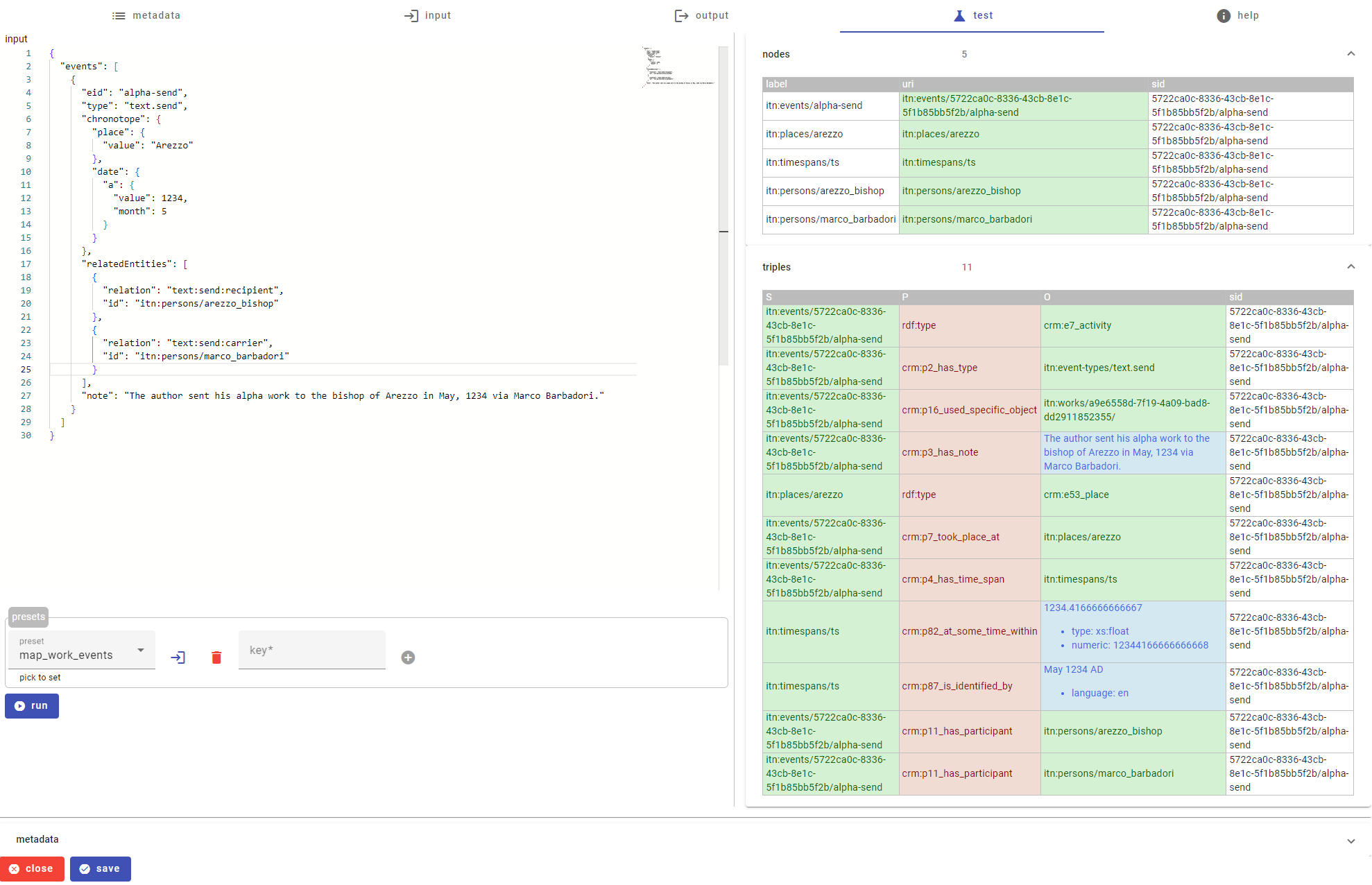

You can test how each mapping works in an interactive mapping editor by using the Graph Studio App. In the screenshot below, you can see the death mapping described above under test:

The test UI is part of the mapping editor. Here you see the full death mappings tree in the left pane. In the central pane, we have loaded some preset data (we can type or paste some JSON here, or just pick a preset datum from a list we can provide and enrich): these are right the data shown above for our example.

Once we load data, we just click the run button to execute the mappings tree. The result is in the right pane, having:

- a list of projected nodes, with their label, URI, and SID.

- a list of projected triples, with their subject, predicate, object, and SID. In objects, the green color represents entities and the cyan color represents literal values, which may have additional metadata like type or language.